The Gift of the Stranger at the Door

Essay | On autistic children, angels, other multidimensional beings, and the thresholds they help us cross.

“Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” — Hebrews 13:2

We all remember stories that remind us to offer kindness to weary strangers because they may be an angel or other benevolent beings in disguise. The old traveler at your door, the poor woman on the side of the road — those who seem to have nothing worldly and can offer no payment but whose presence is the moral fork in the road. We can choose to ignore the stranger or we can invite them in for a meal and to warm themselves at our hearth.

Far from being beggars, the presence of the stranger is simple and devoid of any narrative of grief or victimhood. The angel in disguise at your door asking for shelter from the cold night doesn’t rage if you say no; they simply disappear. The stranger at your door holds no expectations and has no attachment to the outcome of your decision. In that sense, they are timeless and thus …strange.

The dictionary holds two meanings for the word strange:

“Unusual, or extraordinary, surprising in a way that is unsettling or hard to understand.”

“Not previously visited, seen, or encountered; unfamiliar or alien.”

What if the story of the stranger at the door is encoded?

What if we’re not letting them in so much as we’re being let in?

What if that which is extraordinary is inviting us in?

What if the stranger at our door isn’t seeking food and shelter…

What if the Strange is seeking us?

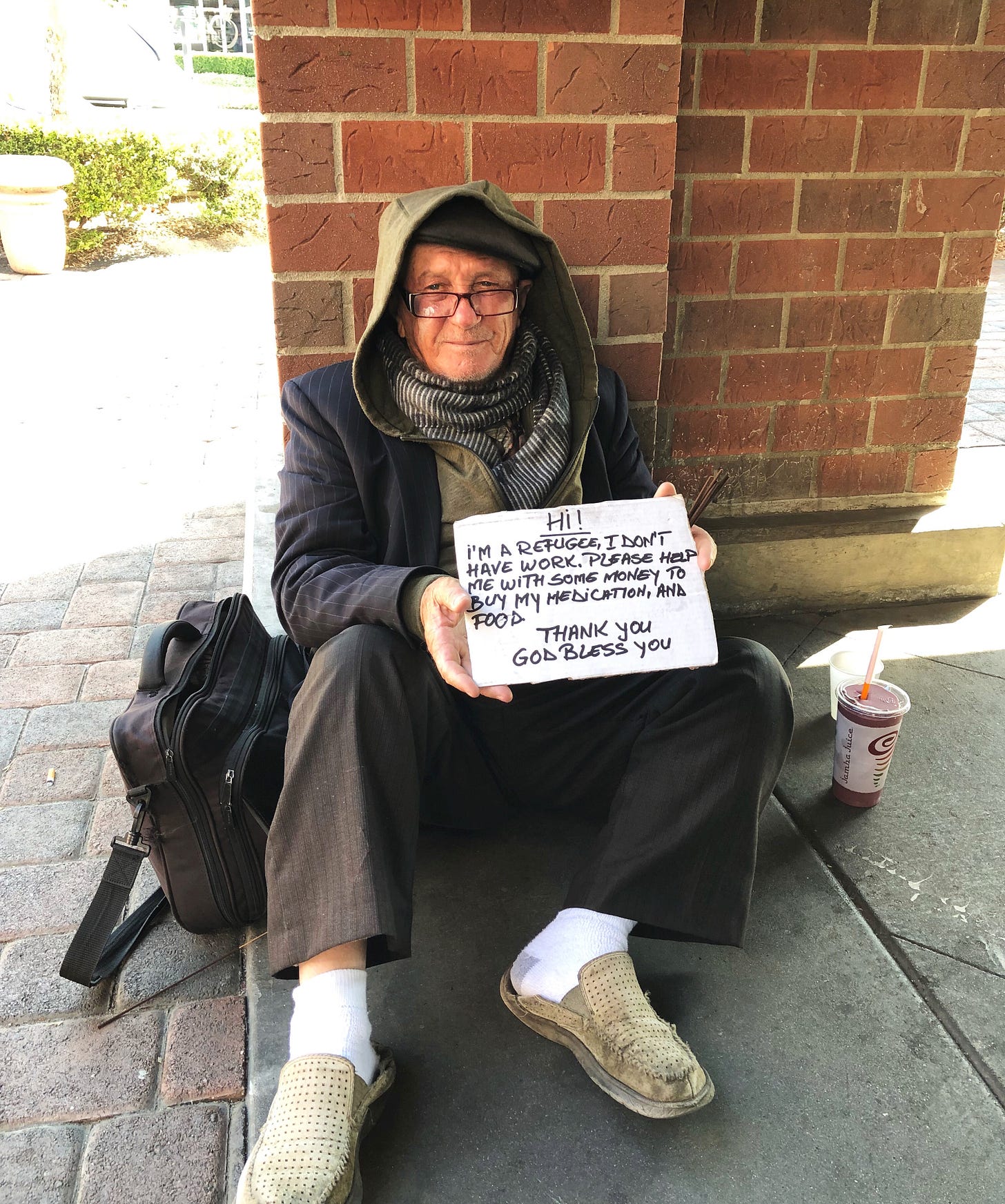

Several years ago I was running errands around in the town I’ve lived in for thirty-five years, long enough to know what’s normal. I was headed into Jamba Juice when from a distance I saw a homeless man in an open corridor outside the shops. Our eyes met as I walked toward him. I would have to pass him on the way, and I didn’t think to skirt around him as one typically does when you assume you’ll be asked something.

My brain didn’t register what was different or strange about him till after, but my heart warmed toward him. He smiled, and I smiled back. There was something about his eyes that is still quite hard to describe. I’ve never felt anything like it. I wanted to walk toward him.

I walked up to him and still, he asked for nothing. He just smiled and held up a sign that said he was a refugee. I asked where he was a refugee from.

“Italy,” he said simply — still not asking for anything.

I scrambled around my possessions, realizing I didn’t have any money to give him. That sense of generosity I felt in that moment wasn’t pity, a guilty conscience of seeing someone with less than that you feel the need to pacify by offering a few dollars. I wanted to give to him. Flustered trying to remember how to speak my long-forgotten Italian, I told him I didn’t have any money but that I’d get him something to drink.

All the while he smiled gently. He asked for nothing. He said nothing.

He simply radiated beauty.

I went into Jamba Juice, got both of us a drink, and returned. It’s at this point I should share that while I write how I write, in my day-to-day life I’m a hot mess. I’m almost always falling over myself and scrambling between the pinball game of things I am trying to do at the same time. That day was no different.

I gave him his drink, which he accepted kindly and set aside. There was no animated reaction, no excitement or delight in receiving a cool drink on a hot day. He simply was graceful ….he was grace.

In broken Italian, I told him I didn’t have any money on me right then, but that I would return tomorrow and give him some. I asked for permission to take his photo, thinking I could also crowd-source funds to help him. He politely agreed, his eyes sparkling a little more with amusement as if somehow I was the strange thing on the side of the shops trying to fit in where I didn’t belong.

As I tried to juggle everything and take a photo, I spilled my drink on myself. He instinctively took out a white tissue and handed it to me. In that moment, I thought for a split second, how could he possibly have had a perfectly folded clean tissue ready to offer…as if this was a stage and me spilling a drink was his cue. Without hesitation and forgetting my aversion to using things people have touched, I took the tissue, thanked him, and walked away.

I didn’t want to walk away, but I figured I’d see him again tomorrow. I thought, tomorrow I’ll invite him to dinner.

Tomorrow never came.

I returned the next day with $50 but our stranger was nowhere to be found. We’ve had a growing issue in our community with homelessness, and you typically see the same few people around. I never saw him before and I never saw him again. Later I puzzled over how he could be an Italian refugee. Italy doesn’t exactly produce refugees anymore and most refugees have resources through a church or some other organization. Only years later did I consider, maybe — just maybe — the stranger was an angel.

In writing this I’m thinking about what gift he brought me, and it’s this: I still feel the warmth of his smile. I can still feel his peace.

The Wild God at our door.

The teachings of Christ say, “Whatever you did for the least of these my brothers, you did to me.” (Matthew 25:40).

Given that Christ is referred to as Lord himself, the passage raises a powerful question: What if the stranger at our door is God?

One of my favorite poets, Tom Hirons, has an exquisite poem about someone very strange showing up at the door. In Sometimes A Wild God, Tom writes,

“Sometimes a wild god comes to the table.

He is awkward and does not know the ways

Of porcelain, of fork and mustard and silver.

His voice makes vinegar from wine.”

The poem unfurls in a wild revelry where everything …falls apart. Tom, who has mastered knowing the wilderness and who leads guided circles on how to walk into a wider sense of the wild belonging, offers the profound idea that the stranger at your door invites us into a letting go, revealing the soul-self by undoing all the layers of our civility, of our pretension.

Shedding — removing what isn’t ours so we can return to where we belong — is also a type of gift, and in many ways a blessing of an encounter with the strange.

Across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, there is a unified belief that God (or the Divine however you choose to define it), reveals through angels in disguise. The etymology of reveal means to “disclose, make known (supernaturally or by divine agency, as religious truth)” — to remove the veil and make visible, to go back to the original place, to undo, the make new again.

The question then is what is being revealed?

What does the presence of the strange remove in our lives?

What is revealed when all the surface layers of life are removed — the comfort of our routines, the frills and decorations, and even the memory of how we used to be once upon a time?

Letting go of the pretension: this is the gift of a strange child.

If you didn’t already know — I’m a mom to a 12-year-old autistic boy who I also started homeschooling in 2020. It’s safe to say that these days, I really am a hot mess as a result of caretaking, homeschooling, managing his appointments and activities, and trying to finish several more books. These days, I rarely look in the mirror because I don’t recognize myself, feeling like a shell of the woman I used to be. My clothes are always stained. My hair is a mess. I don’t have the time or energy for makeup, and I always look…tired.

Last week, I was sitting in a waiting room for over an hour, slumped back in my chair when I looked up and saw the security mirror high up on the wall like a giant silver bauble. A great unrelenting glass eye that I couldn’t look away from. There I was, shapeless…and tired. Next to me, was this strange magical little boy who is always with me like a daemon or a familiar — my other half, the shadow that never leaves my side. The strange being at the figurative threshold of my existence who greets me every morning with stars in his eyes and a smile so wide it squishes his cheeks. My gift.

Being an autism mom is an act of service and devotion that pulls you into the sacred — to shed what is no longer of you or for you. When the mythic speaks of Inanna, the Sumerian Goddess of love and war who shed her crown and garments to descend into the underworld for her sister, I know what it speaks of. When beloved author Paulo Coelho speaks of walking on your knees in pilgrimage, I know what he means. Autism parents walk on their knees every day toward the threshold where the strange knocks.

The outer world doesn’t understand this. The outer world has forgotten the language of devotion to service, to answering the call, to welcoming the strange.

Well-meaning people will ask me, “What do you do for yourself” to which I want to say: I decompose. When I have some time to myself, I just want to sit there for a minute and decompose into nothingness. I want to forget how to use porcelain and silver. I want to simmer in vinegar.

It took me till about four hours ago to realize this too is a gift of the strange.

Strange, weird, unfamiliar — these are the sentiments plenty of people (family included) use to describe my autistic child. It’s said out loud in the space between things, between looks and inaction, even if it’s never actually literally said aloud. Who’s to tell them that even unsettling feelings are a gift — a gift from our strange children who remember what it means to belong to a Wild God?

Each discomfort is a knock in the dark of night. The gift simply disappears if you don’t meet at the threshold of a strange wilderness rapping at your door. The presence of an autistic child — like the presence of a stranger at the door — makes some people feel unsettled. Unsettled by the unfamiliar. Unwilling to let the strange into their hearts. Unwilling to accept the gift of the stranger.

Rewilding Childhood

Autism families are always searching for tools and resources that can help them better understand and manage the day-to-day reality of Autism. What I found in my experience as an autism mom is that when I embraced being his mother, caretaker and teacher — because there was no other choice but to do that — I moved deeper into welcoming the gifts of the strange into my life, gifts that yield thought-provoking writings.

As much as I was leading my son, he was always — and had always been — leading me too. That reciprocal relationship, unveiling the blessings these children bring in disguise, is what I nurture through Rewilding Childhood.

These children are not broken children that need to be “fixed.” They are strangers at the door who bring an invitation to let go, to rewild ourselves back into the wider field of possibility of what it means to be human. The blessing and the challenges of being an autism parent is a type of revelation that is an undoing, a sacred falling apart. Yes, this is hard — but it is also beautiful.

If you’re a parent of an autistic child, I invite you to join our private Facebook community, Rewilding Childhood. We have a growing online community, and online and in-person gatherings where we celebrate our strange little world. If you’d like to offer a contribution to support my writing, I welcome the gesture and thank you.