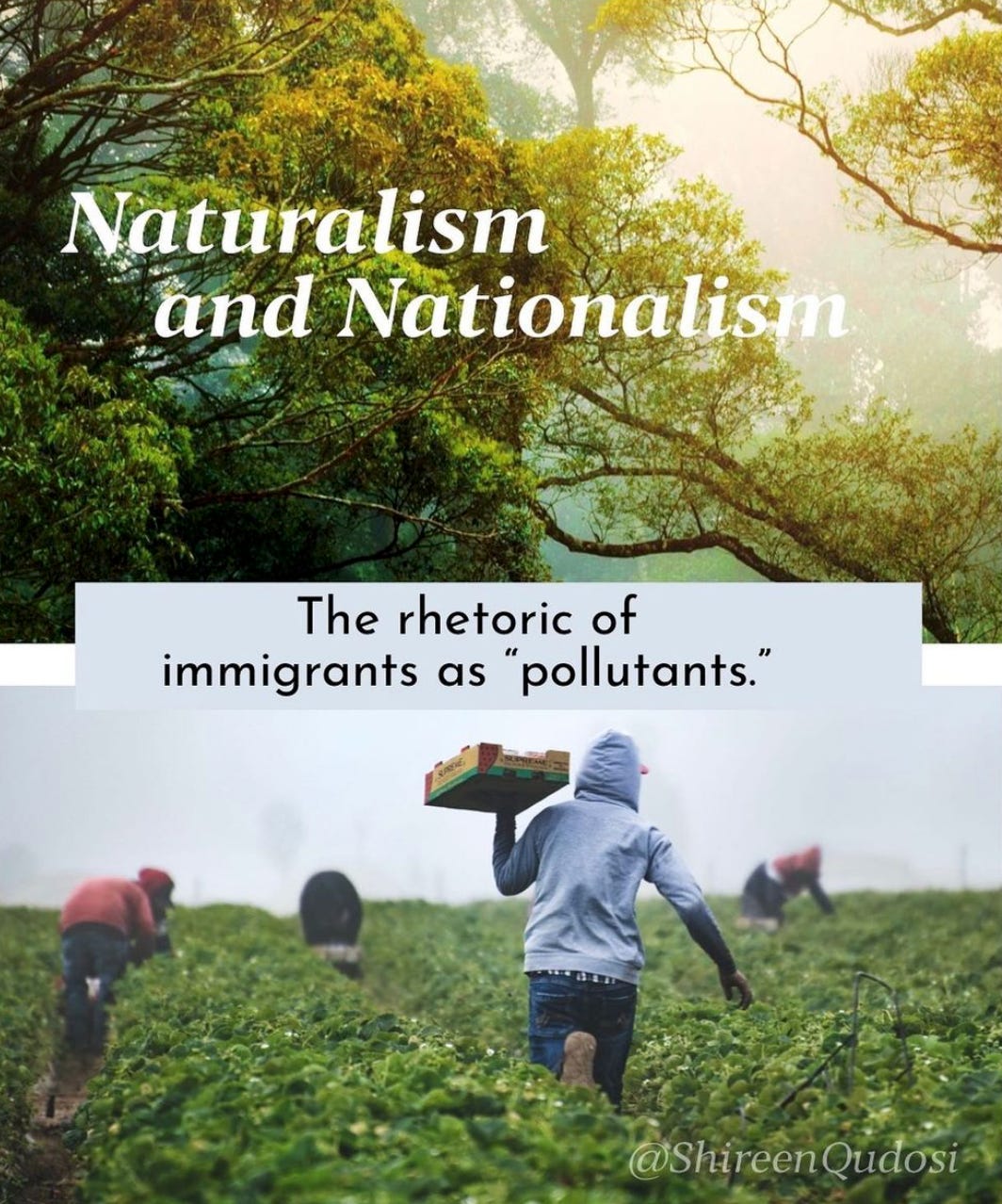

The Rhetoric of Immigrants as "Pollutants."

Naturalism and nationalism in a resurfaced wave of open race supremacy.

The latest on intersectional nightmares is a pairing of environmentalism and white supremacy, rooted specifically in the language of the former to advance the agenda of the latter. Throughout the last century and moving through our present time, the rhetoric of toxic nativism shaped anti-immigrant, anti-minority and anti-Semitic narratives. Today, it is no different. As ideological propagandists have discovered, it is much more savvy to conceal hate through virtue signaling than to outright declare their hate.

In this essay, I take you through some of the research and findings to stitch together a portrait of how toxic nationalism and white supremacy operates in our time under the banner of environmentalism, and how there is very little difference between the tactics today and the tactics used by older outrightly hateful regimes.

Earlier this year, author Beth Gardiner published a New York Times op-ed in which she points to the shared rhetoric between the two ideologies as environmentalism gained mainstream acceptance in the 1970s (and as it continues to inch further from sound conservation to its own form of extremism:

"[white supremacists, who argued that those they saw as outsiders threatened the nation's landscape or lacked the values to care for it properly. Such thinking was common in Europe, too. The Nazis embraced notions of a symbiotic connection between the German homeland and its people."

However, language referring to landscape and culture, along with concerns over immigrant populations, are not guaranteed signifiers of white supremacy. Along the way there have been genuine concerns around nationalism and preserving a sense of identity, though that identity has and continues to be debated and shaped in an evolving conversation. Nonetheless, a desire for preserving some nostalgic sense of self as a collective people doesn't make someone a white supremacist. More nuance is required including a look at how in very recent years toxic nationalism and white supremacy have increasingly adopted the language of nationalism, blurring these lines even further.

Simply put, accusations of white supremacy are a blunt instrument (not that dissimilar from how accusations of Islamism have also often enough been a blunt instrument to demonize a population or competitor).

Peter Beinhart, professor of journalism at the City University of New York, would disagree. In 2019, Beinhart published a piece inThe Atlantic on how far-right propagandists have seized environmental treats as, "another means of sowing racial panic." Beinhart writes,

"What we’re witnessing is less the birth of white-nationalist environmentalism than its rebirth. In earlier periods of American history, nativism and environmentalism were deeply intertwined. The Nation recently reminded readers that Madison Grant, who in the early 20th century helped found the Save the Redwoods League and the National Parks Association, also served as vice president of the Immigration Restriction League, which successfully lobbied to cut off most eastern and southern European immigration to the United States in 1924. Grant, whose 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, proposed a racial hierarchy of European peoples and greatly impressed Adolf Hitler, saw no contradiction between his environmentalism and his racism. To the contrary, wrote his biographer, Jonathan Spiro, he 'dedicated his life to saving endangered fauna, flora, and natural resources; and it did not seem at all strange to his peers that he would also try to save his own endangered race.'"

Beinhart follows the threat in his article linking 20th century patterns to modern political ideologues and their distasteful rhetoric saturated in xenophobia. It's debatable, again, whether that in and of itself makes them white supremacists let alone neo-Nazi aficonados.

Gardiner pivots attention to another emboldening merger between environmental activism and neo-Nazi groups:

"The neo-Nazi group Northwest Front, which advocates expelling people of color from the Pacific Northwest, appropriated a flag designed by a left-wing activist, reframing it with the slogan “The sky is the blue, and the land is the green. The white is for the people in between.”

Quoting John Hultgren, a faculty member Bennington College, Gardiner shares how the reality of global warming or climate change by those who chose to acknowledge it, is then seen "through the prism of white nationalism. And the solution then becomes the exclusion of immigrants, people of color, and the so-called 'Third World."

That assessment puts a spotlight on Beinhart's piece, raising far overdue questions about how this point differentiates a supremacist ideology from its more splintered parts. Perhaps the answer to that lies in rhetoric versus action -- in other words, radicalization vs extremism. Who believes in the ideology, who is actively executing the ideology, and is the rhetoric of the former responsible in anyway for the latter. The latter in this case are the violent extremists on the streets. And even that still leaves wide open a question of what is worse, psychological extremism or its kinetic eruption through chaos agents -- or both?

This is where acceleration comes into play given there is likely a causal relationship between the two. Is the language from those with wide-reaching platforms responsible for emboldening and activating extremist violence, nearly all of whom support the idea of an end-all war in a culture of hyper-polarity?

It becomes harder to sever the past and draw borders around the fiction of neat identity markers when the line between the past and present, between malevolent supremacist ideologies and 20th-century offshoots, is ever thinning. At the very least, the convergence of extremist ideologies then and now demands unapologetically bold questions, especially when the Nazi slogan of "Blood and Soil" was chanted during the 2017 Charlottesville rally.

Writing for The New Republic, Sam Adler-Bell shares how the rhetoric of "Blood and Soil” predates the Third Reich and is rooted in antisemitism. Later, we learn how that antisemitism is entwined with 21st-century white supremacy also veiled as environmental interests:

"The Nazi slogan 'Blood and Soil' reentered public discourse two years ago, when torch-wielding neo-Nazis chanted it in Charlottesville. But the phrase actually predates the Third Reich. In the nineteenth century, German romantic writers like Ernst Moritz Arndt and Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl synthesized naturalism and nationalism. 'We must save the forest,' Riehl wrote in 1853, ‘not only so that our ovens do not become cold in winter, but also so that the pulse of life of the people continues to beat warm and joyfully so that Germany remains German.’”

This philosophy later inspired the Völkischmovement, a youthful revolt against capitalist modernity that preached a return to the land, and to the wholeness, purity, and plenitude of rural peasant life. In the 1920s and ’30s, veneration for the earthbound volk—and hatred for its opposite, the rootless, urban Jew—found their way into Nazi ideology, where they were infused with scientific racism and transformed into a rallying cry. 'The concept of Blood and Soil gives us the moral right to take back as much land in the East as is necessary,' wrote Richard Walther Darré, the Third Reich’s minister of food and agriculture. He spoke of Jewish people as 'weeds.'"

Last year, I covered the conscious attempts by ideological extremists to the ideological war under the theory of acceleration. According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), "Accelerationism is a term white supremacists have assigned to their desire to hasten the collapse of society as we know it."

Gardiner also introduces Blair Taylor to the conversation. Taylor, who is a program director at the Institute for Social Ecology, speaks to the theory of acceleration within the context of environmentalism and white supremacy. Taylor notes the desire to accelerate conflict is linked with what is viewed as an opportunity to set up "fascist ethno-states" after the downfall.

The acceleration Gardiner and Taylor speak of is anchored to the rhetoric of immigrants (specifically people of color) being pollutants. In the last several years, the rhetoric of immigrants as pollutants were seen from the highest office in the land, the presidential pulpit, when non-American minorities were referenced in the context of policy agendas.

"For [white supremacists]...the nation is an ecosystem, and non-white immigrants are an invasive species." - Sam Adler-Bell, Why White Supremacists are Hooked on Green Living

While there isn't a direct connection, of course, its important to note that it does appear elsewhere, including among violent race supremacists. As Gardiner accurately notes,

"The killers accused of targeting Muslims and Mexican immigrants last year in New Zealand and Texas posted online manifestoes weaving white supremacy with environmental statements. The Australian man who allegedly murdered 51 people at two Christchurch mosques called himself an 'ethnonationalist eco-fascist' and wrote that 'continued immigration into Europe is environmental warfare.' The suspect in the El Paso shooting that killed 22 — modern America’s deadliest attack targeting Latinos — ranted about plastic waste and overconsumption. 'If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can become more sustainable,' he concluded."

This isn't just an American problem.

French far-right leader, Marine Le Pen, described a French citizen as "someone rooted, someone who wants to live on their land and pass it on to their children," adding that the "nomadic...do not care about the environment. They have no homeland."

In 2019, France's far-right National Rally (RN) -- the opposition party led and recently rebranded by Le Pen -- launched a climate change policy platform in which its ideological leaders have continued to cloak supremacists belief systems within the socially palatable package of environmental consciousness:

"Borders are the environments greatest ally. It is through them that we will save the planet." - Jordan Bardella, RN spokesperson.

"The main threat we face now comes from the collapse of our environment." - Herve Juvin essayist.

Juvin also refers to "the people of European Nations" as "indigenous people," which is an exploitive manipulation of the term indigenous in its original context.

In the UK, far-right group Generation Identity looked for ways to make the groups message on remigration (the deportation of migrants and non-white people) mold into a message on the environment. This was around the same time the group launched a "Local Matters" campaign to encourage economic resiliency during the Covid-19 lockdown. As Vice reports, even that campaign was rooted in identitarianism that masked a concern over homogeneity with feigned care for the lives of third world immigrants.

The issue of local matters is relevant beyond the campaign. Back in the United States, a story broke last year identifying a pair of small-town farmers as white supremacists affiliated with the hate group Identity Evropa. On the weekends, the local farmers sold produce at a farmer's market, while also being involved in chat groups that fear-mongered against neighborhoods with minority residents and embraced Nazi rhetoric that labeled non-whites as inferior.

While white supremacists use eco-rhetoric to push race separatism, seeing themselves as unique to the land, it is impossible to ignore the ecosystem of hate that connects the radical beliefs of private citizens with populist figures and national movements.