Yawanawa Tribe's Song Rituals Expands Belonging in Faith

Podcast | Mapping a feminine Islam that is fluid and interplays with all elements of life, especially the vibrational reality of sound.

The following podcast is an excerpt reading from The Song of the Human Heart: Dawn of the Dark Feminine in Islam paired with audio recording from the Aniwa Gathering 2022, recorded and shared with permission from the Yawanawa tribe.

Aniwa is an annual gathering of 40 indigenous leaders from around the world. “We are slowed down sound and light waves, a walking bundle of frequencies tuned into the cosmos. We are souls dressed up in sacred biochemical garments and our bodies are the instruments through which our souls play their music.”

“We are slowed down sound and light waves, a walking bundle of frequencies tuned into the cosmos. We are souls dressed up in sacred biochemical garments and our bodies are the instruments through which our souls play their music.”

— Albert Einstein

The Song is the Medicine

In the summer of 2022, I attended Aniwa in the mountains of Big Bear, California. Aniwa is a gathering of wisdom keepers that brings 40 of the world’s foremost indigenous leaders and elders together across several days.

On the fourth day, four members of the Yawanawá1 hosted a song workshop. Two men and women not past their early twenties guided our group through the various sacred songs5 of the Yawanawá tribe. All members of the tribe ask the forest to teach them song medicine. Every new generation learns these chants in the forest paired with fasting so that they can be present with the words of the song.

The elders teach that every bird in the Amazon has a song, no matter how melodious or alarming. It doesn’t matter if you don’t have a traditionally beautiful singing voice; every singer is welcome. The guides shared with us their belief in how a force comes in when they’re in song and when they’re with plant medicine. If there is a spirit, it is with them when they are in song.

The voices of our guides are youthful, reflecting their young age and even their hesitation to be up on the stage with the usual sort of showmanship we’re used to seeing in TED Talks. This is simpler, a sort of force that is already stirring between the drums, the speakers, and the patterned canopy overhead.

The first song is of the men, a deep bellowing grounded chant of two verses that say: We are here, but we are on our way. It speaks to the beautiful quantum reality that I found Islam also speaks to — that you can be in two places at the same time. The second song is for the women and expresses a beautiful lament, a remembering as haunting as a wolf’s call.

The songs are simple and learned in their traditional form, after which tribe members are welcomed to innovate the songs through their own musical signature. Each person can create a new version, a new branch of the original song. The song is always renewing itself through the singer. It reminds me of the intention religion carries, offering a template for our understanding of the world but also allowing for the flexibility to adapt and bend — not to our will out of force but through play. Like a swinger of birch trees swaying to and fro on branches that bend to the ground as children play on them, creating new forms and patterns in the silhouette of trees, a new kind of belonging across a landscape that is the unique expression of the artist — the swinger. As poet Robert Frost said, “One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.”

The traditional men’s song of the Yawanawá is not unlike the Islamic azan. It feels like an instruction, something you stand there and receive. The innovation of the men’s song by one of the young tribesmen was entirely different. He paired the song with drums and guitar, infusing a new rhythm that was joyful, and celebratory. Here now, you’re not just with the traditional song, you’re also hearing the response to the song. The innovation answers the question of the wild, “Where are you?”2 You’re answered with the spirit of play, through fun and frolic. Faith is the simplicity of a child in play, inflow for the sake of play rather than any end destination — like a song.

Through innovation, you hear the beauty of unique expression. You hear the interpretation of a tradition, a novelty that is entirely his own imprint on a legacy. It is nothing short of masterful, enriching a deeper sense of belonging that is not just present but also inclusive. We all began dancing and singing. The Yawanawá punctuate the song with short random callouts that are part of their cultural practice. They resemble what you hear among Arabs during their celebrations, an ululation that is a high-pitched vocal sound except here it’s much shorter. For the Yawanawá, like the Arabs, it’s an invitation that welcomes reciprocation — something my son Reagan Azan who is on the Autism spectrum also does in moments of elation. Here he would be welcomed, I thought. Here he could belong.

Where the men’s song shifted from stoic to receptive, the women’s song moved from sounding like a prayer in traditional form to sounding like a longing for love in its innovation. Accompanied by a slower tempo in guitar and drum, a voice that carried so much gravity than its tender years, sang of a wisdom and tenderness I hadn’t found in traditional Islam. In some ways, hearing her sing her lament, and the lament that echoed the wail of the Common Loon3, unlocked a memory within me of something I didn’t know I had lost and yearned so deeply for. The song I was listening for was in some ways also the lament of my own heart, my own heartbreak at never finding belonging anyplace except in spaces between things.

In all the inquiry into which interpretation in Islam is legitimate, the battles over who did what and when, we lost the sacred (that was uniquely for us as pilgrims of the heart in the journey toward the all-loving God). And yet, here I’m listening to a girl half my age who belongs to a remote culture that on the surface level was completely different from Islam. In her song I found something I couldn’t find in the surface layer of Islam despite 20 years of searching through Islam for what was missing. I was searching for something I couldn’t name, for the song that exists because we existed; for a song that could only ever be because you came into the world. I was searching for the existence of what rises when you feel like your journey has failed you, and is failing you. When it's just you in the spaces of nothingness, what song does your heart sing? What would that song sound like if you had also been taught by the birds? I was in some way long since searching for the song that is cast in the Dark and heard by all that belongs to the wilderness of the heart.

“The song is the medicine of the birds,” we’re told by Rasu, one of the four members of the Yawanawá.

“My father said in the forest we learn from the birds that some birds are soft, some strong, with different calls and different stories. If singing from the heart and believe in what you’re singing — that’s all that matters. In the forest, we are all singing, women, men, children, elders, and leaders. The more people are singing, the more the world can heal.”

The view of medicine is different in indigenous cultures, seeing medicine as something that offers the nourishment of wisdom, preventing a weakened spiritual state much like the nourishment from food prevents a weakened physical state.

For the Yawanawá, song learning is not complete until singing together, which is how we closed the song workshop. A chorus of people rising to stand, and learning a song for the first time, stretching their voice into new forms that danced to the beat of a heart in elation. By the end of our song, I was holding back tears. I thought of my own life, a blur of ten-hour work day, a son I don’t nearly get to spend enough time with in a way that really matters, in a way that we both deserve. This could be life, I thought. This is the life we all deserve — a life of song and elation and gathering. Instead, we’ve accepted a placebo devoid of the richness of the ceremony of being in community — a ceremony where we celebrate the signature of our expression, where we cast our song. A life where there is always an answer to, “Where are you?”

The richness of voices of the young Yawanawá doesn’t mirror their age. The young men sound as if they are decades older, and the young women sang with a wisdom you hear in the voice of women far more mature who have suffered the sting of loss. The songs have been sung for a very long time and everyone’s song is different. How many times have I heard the Islamic call to prayer, the azan, recited but unsung? How many times has it been recited but never made our own? What could we learn from the Yawanawá to enrich our own experience with faith?

There are so many ways to worship in the world, so many ways to call out in the darkness. But there’s also another calling, a calling that says, “I am listening.” In between all the noise, where is the absence of sound? Where is the silence? What is the silence singing? Can you stay with that song of silence, and listen for it for as long as it takes?

We have scripture and prayers in Islam as with most other faiths, but no song. There is the Azan, a recited announcement letting the community know it’s time for the first of five prayers of the day — or now with the tech age, through the shrill metallic cry of the prayer app on your phone. The fajr (dawn) prayer is not a song; it's a call to attention. And yet there are those of us whose hearts are of the wild, who resist submission to an obligation. The call of the Wild cannot be summoned. Presence cannot be drummed up through a duty to be present without losing what is sacred in that arrival.

There is a richness to the song when it is of free will. When a free heart recites the Quran, it is not a recitation — it becomes a song. It is no longer a verse, it is music. It is religion made sacred in that moment for that moment. Though there are beautiful recitations that are song- like, the Azan is not treated as something to be sung. It’s recited from memory of mind. There are exceptions who when they sing glow radiantly like orbs in the night sky scattered like seeds upon which we trace lines to create a map of what makes humanity sacred. A song is unique, and a culture that sings carries a different tune, a different frequency that can shape and reshape the world.

A book 42 years in the making…

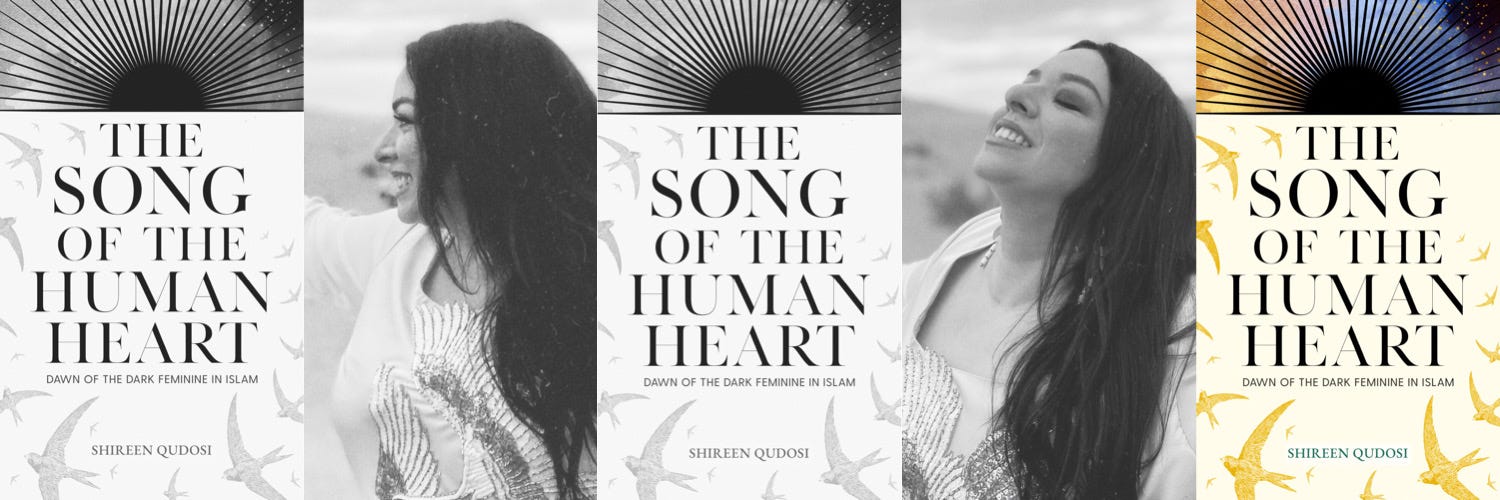

The Song of the Human Heart:

Dawn of the Dark Feminine in Islam

Islam is often called a ’dark religion’ by those who have misunderstood the faith. The Song of the Human Heart encourages embracing Islam as a ‘dark’ religion. Islam belongs to the realm of the Dark, the primordial feminine aspect of God. The Dark is the other eye of God alongside the Light, across a face of a great divinity that is nebulous and unknowable.

The Song of the Human Heart is a return to belonging and remembering the intimacy of what it means to be human. The book I started feeling for after 9/11, The Song of the Human Heart is crafted storytelling that turns decades of lived experience into a constellation mapping the way back home to The God-Heart.

The Yawanawá, known as ‘the people of the wild boar’, live in the Indigenous Land of Rio Gregório in the state of Acre, deep in the Brazilian Amazon. (Elms)

Greg Budney, Macaulay Library Audio Curator, describes the song of the Common Loon in the North Woods. (Macaulay Library)

Common Loons are freshwater birds that produce loud, long, haunting vocalizations during the breeding season, usually at night. The wail often sounds like a wolf's howl. (Beletsky and University)